Letting people take part in the electoral process—that is, voting—gets them involved and engaged in how their town, province, territory, or country is run. In Canada, only Canadian citizens aged 18 and over can vote. But is that fair?

In 2009, there were 252 179 permanent residents living in Canada.![]() That means 252 179 residents without the right to vote, despite their paying municipal taxes and using services and facilities such as education, child care, libraries, transit, and parks. “I continue to pay taxes and to participate equally in community issues like my friends [who are] citizens. But, when [it] arrives to choose who will represent us, I cannot vote because I am not yet a citizen. This is not fair,” says Asumani Serugendo, who arrived in Canada in 2007.

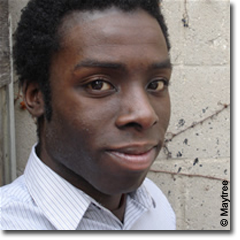

That means 252 179 residents without the right to vote, despite their paying municipal taxes and using services and facilities such as education, child care, libraries, transit, and parks. “I continue to pay taxes and to participate equally in community issues like my friends [who are] citizens. But, when [it] arrives to choose who will represent us, I cannot vote because I am not yet a citizen. This is not fair,” says Asumani Serugendo, who arrived in Canada in 2007.![]()

|

| Desmond Cole, former co-ordinator of I Vote Toronto |

I Vote Toronto

I Vote Toronto is a campaign that is pushing for non-citizen municipal voting rights in Ontario.

Former co-ordinator Desmond Cole says that by engaging newcomers in municipal civic life as soon as possible, we’ll help them feel that they belong, and hopefully entice them to continue to participate in the electoral process and civic life.

This community coalition, he says, “want[s] to change how we vote. You have to be a Canadian citizen to vote in a municipal election in Ontario, and that’s the way things have been for a long time. We’re asking the province if they will change the law so that permanent residents of Canada who are on the path to citizenship can […] vote for their city councillor, their mayor, and their school board trustee.”![]() Newcomers’ votes will help make government and school boards more responsive to their needs, and consequently, those of the entire municipality.

Newcomers’ votes will help make government and school boards more responsive to their needs, and consequently, those of the entire municipality.

“[T]rying to convince people that extending this right is not simply giving something away for free, but that it has a benefit for the newcomers, [and] for the entire community,” is a challenge, says Desmond. Some opponents say that giving these voting rights to non-citizens cheapens Canadian citizenship.

However, with the successes of over 40 countries around the world (e.g., New Zealand, Belgium) who already extend municipal voting rights to non-citizens,![]() and the support of over 70 organizations and thousands of individuals for the I Vote Toronto campaign, Desmond hopes that the next round of Ontario municipal elections will be voted in by permanent residents, too. The rest of Canada is watching.

and the support of over 70 organizations and thousands of individuals for the I Vote Toronto campaign, Desmond hopes that the next round of Ontario municipal elections will be voted in by permanent residents, too. The rest of Canada is watching.

1 Source: Citizenship and Immigration Canada, RDM, Preliminary 2010 Data |