|

| Shannen Koostachin giving a speech |

Shannen Koostachin, from the Attawapiskat First Nation reserve, had a very simple dream: she wanted all First Nations students to have the chance to get a good education in a “safe and comfy school.” It sounds simple; but in fact, this dream is out of reach for Shannen and for many First Nations students living on reserves. Our Constitution guarantees First Nations a right to an education equal to that provided for other Canadians. Why are they not getting it?

The answer lies in the history of First Nations education in Canada, the cultural needs of First Nations students, and the unequal funding that goes to First Nations education.

|

1. The History of First Nations Education

Until the 1970s, schools for First Nations students were tools used to make them a part of Canadian culture. The focus was not on a good education. The focus was on destroying their cultures and languages.

When First Nations communities gained the right to run their own schools on reserves (1970s to 1990s), they had no experience. They did not receive any support from the federal government in the form of new laws to say how the schools should be run. This meant no support with developing curriculum and training teachers, principals, supervisors, and other education leaders—the whole structure that makes a school system work.

Compare that to school systems in the rest of Canada, which had been operating with outlined roles and rules for more than a hundred years. Right from the start, there was a gap between the two school systems. And that gap persists today.

Shannen’s School

What does this mean for First Nations students every day? In Shannen’s case, it meant her elementary school, located along the James Bay coast in Ontario, was not safe or comfy. Her school was made up of a bunch of drafty, rundown portables alongside a noisy airplane landing strip. The portables were freezing in the winter—especially when the heat stopped working.

Shannen’s school, J.R. Nakogee School, is a collection of portables.

The Attawapiskat First Nation reserve did have a proper school once, but the brick building was shut down when people discovered it had been built on thousands of litres of diesel fuel. (A toxic spill had taken place there 30 years earlier.) The portables were supposed to be a temporary solution until a new school could be built, but nine years passed with no new school.

Shannen thought the situation was unacceptable. She wrote letters to the federal government requesting a new school, and she inspired thousands of students from all across Canada to write letters, too. In 2008, Shannen met with Chuck Strahl, the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) at the time, to demand a new school. He replied that there wasn’t enough money in the budget to fund a new school on Shannen’s reserve.

2. Cultural Needs of First Nations

Why wasn’t there enough money for a school on the Attawapiskat First Nation reserve? First Nations education gets plenty of funding—in 2008 about 1.2 billion was spent on First Nations education for 120 000 students living on reserves. But an awful lot has to be done with that money. Many First Nations schools on reserves lag behind the rest of Canada when it comes to teacher training, curriculum development, and testing. It takes a lot of resources to bring these areas up to date.

|

|

| These children are learning their traditional language. |

|

First Nations schools also struggle to make school culturally relevant for their students. This means taking learning outside the classroom to include learning from family, the community, ceremonies, traditions, and the land. It also means bringing traditional practices inside the classroom—all of which costs money.

3. Unequal Funding

Added to the problem is the fact that the INAC funding formula for First Nation schools hasn’t changed since 1996. Today, First Nations schools on reserves receive, on average, $2000 less per year for each student than provincial schools.

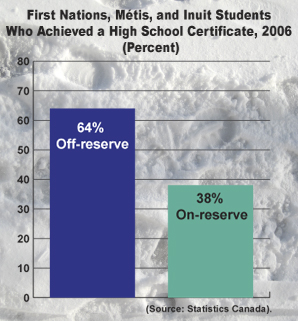

Is that fair? Many First Nations education advocates say “no.” That gap of $2000 per student could help to improve the system and make classrooms more relevant to students’ lives. Is the gap having detrimental effects on First Nations students? First Nations education advocates say “yes” to this question, and diploma and graduation rates seem to back them up. Check out the graduation rates of Aboriginal people living on reserves and off reserves.

According to Free The Children, high school graduation rates don’t tell the whole story of First Nations education but they do “…hint at a deep gap in the opportunities open to First Nations youth on-reserve versus students in provincial, territorial, and private schools.”

The federal government, to its credit, is addressing some of these concerns. In addition to the annual $1.2 billion funding, INAC invests $200 million each year to support the construction of new schools and facilities and the renovation and repair of existing schools, and the design and planning of new projects. In 2008, INAC also announced two more programs from which First Nations Bands can apply for funding: the Education Partnerships Program and the First Nations Student Success Program.

The federal government and the Assembly of First Nations have also set up a group to review the funding formula and recommend changes. As of 2011, the funding formula had not been changed. It appears that INAC is trying to improve education for First Nations, but there is a long way to go.

Shannen’s DreamWhat about Shannen’s simple dream of a new school? In 2009, Chuck Strahl, the Minister of Indian Affairs, promised students of Attawapiskat First Nation a school by 2012. Tragically, Shannen won’t be here to see her dream come true. She died in a car accident in 2010 at age 15. But her community has taken up her fight, and they will not rest until they get a new school. We should also take up the fight alongside Shannen’s community and others like it, by reminding our government ministers that everyone has a right to an equal education in our country.